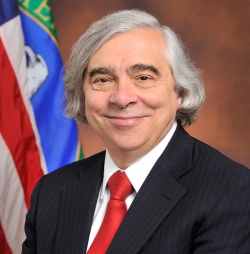

Four new nuclear reactors are under construction in the U.S., the first plants to be built in 30 years. Yet U.S. Secretary of EnergyErnest Moniz says when it comes to nuclear power in the U.S., “the long term trajectory remains quite uncertain.”

Four new nuclear reactors are under construction in the U.S., the first plants to be built in 30 years. Yet U.S. Secretary of EnergyErnest Moniz says when it comes to nuclear power in the U.S., “the long term trajectory remains quite uncertain.”

Moniz speaks to Here & Now’s Jeremy Hobson on a wide range of energy issues and says he expects wind, solar and other renewables to make up 30 to 40 percent of the country’s energy mix by 2030.

On the importance of nuclear power to the U.S. energy future

“Nuclear power, clearly, is one of the important so-called zero-carbon options. It does not emit carbon dioxide, obviously, as does fossil fuel combustion. So our view remains that A, we need to go to a low-carbon energy system over these next 10, 20 years. The solutions for a low-carbon system will look different in different places. Some countries, including industrial countries, will not have nuclear. Others will continue to grow it because it is one of the low carbon options, and different societies have different public attitudes but they also have frankly just very, very different core energy resources. So it will be multiple solutions in multiple places and nuclear power, I expect, will be part of that mix.”

On whether thorium should be used as a nuclear power source

“Thorium is certainly an alternative. I personally don’t see a strong motivation for the United States to move to thorium at the moment. We certainly are not constrained by a lack of uranium, first of all. Second of all, if we go to thorium we would have to go to what’s called a recycling approach because thorium itself does not produce energy. You have to make uranium 233 out of it. So personally, I believe that right now the issue is to see how these new plants perform, in particular in terms of their cost performance. And we have plenty of uranium to continue with our current cycle.”

On whether the fracking industry got ahead of the regulations

“I think we should not underestimate the strength of the regulations in many states. Clearly it’s been largely state-based. As the number of wells drilled increases dramatically, clearly the regulatory regime is evolving with it. But I don’t think we should overestimate that feature that you referred to. It is true that the production has expanded very very rapidly and it’s had a number of issues. For example, the energy infrastructure has not really been able to quite catch up — that’s developing. It’s largely in the hands of the private sector. But we have to also recognize in this discussion the enormous economic impact that this has had, first of all, not only in terms of having much more modest natural gas prices than we had years ago, for implications for consumers, for industry – it’s driven new manufacturing. And secondly we should also remember that the natural gas revolution, if you like, principally through its substitution for coal in electricity, has accounted for a significant part of our reduced carbon dioxide emissions. So we’ve had environmental benefits, we’ve had economic benefits. We have to, at the same time, continue to work to keep reducing the environmental footprint of production.”

On when solar and wind will represent a significant part of energy production

“The growth has been very dramatic, really. In the last four or five years, we have seen a doubling of wind and solar. We expect another doubling over the next several years. Last year we had 2,300 megawatts of large-scale solar alone put in place. What we are seeing with wind — in particular on-shore wind — and solar, is that costs have come down pretty dramatically, and with that cost reduction is coming rapidly-increased deployment. Now obviously, in both cases, we’re talking with relatively small market share today — a few percent for wind and still less than 1 percent, I believe, for solar. But the rate of growth is very dramatic. I mean, we are looking by 2030 to having a very very large fraction of our capacity in wind, solar and other renewables… 30 percent, 40 percent.”

On the issue of nuclear waste disposal

“With regard to nuclear waste, this clearly remains a major challenge. The administration and I personally continue to think Yucca Mountain is not a usable solution, but rather a consent-based process, as was recommended by the Blue Ribbon Commission on America’s Nuclear Future, is the right approach. And that report and the administration’s recommendations are that we start to pursue in parallel, not only geological repositories for very very long-term storage, but also consolidated storage where where we can start moving fuel away from nuclear reactors, presumably under federal control, so that we can have substantial — maybe 50 to 100 years scale — storage prior to implacement in a repository.”