By Eric Viola, WCTA Public Policy Analyst

Introduction

Carbon pricing is the practice of assigning a cost to carbon emissions. There are two basic forms of carbon pricing:

- Cap-and-Trade: This system creates policies that allow a government to place a cap on total emissions. Permits are issued to allow emissions up to that limit. The market then establishes how the limits will be achieved by allowing the holders of the permits to trade them. A firm that can reduce emissions at low cost, for example, can do so, then sell its permit to another firm that has higher costs.

- Carbon Tax: This is a policy that places a tax on the carbon content of energy sources. It taxes carbon directly at a point in the fuel’s life cycle.

The rationale behind carbon pricing is that it shifts back to carbon emitters some or all of the cost of the negative externalities caused by CO2. If the full cost of externalities can be accurately measured and charged to those who produce them, then incentives are created to reduce emissions. The true cost of an externality is difficult to determine, since externalities may manifest years or miles away from when and where they took place.

One of the key advantages of carbon pricing is that it discourages emissions while simultaneously making alternative energy sources more attractive. Instead of implementing a vast, complicated network of subsidies to alternative energy, carbon pricing makes it more expensive to produce carbon—and cheaper to seek out alternatives. Carbon pricing utilize market forces, shifting them so that the price of carbon reflects the costs of greenhouse gas emissions. Proponent of the carbon tax argue that it is relatively simple to implement.

At the other end of the policy spectrum are command and control policies, which are government-mandated regulations that set exact limits on specific emitters or on sectors as a whole. Command and control policies are largely regarded as being more difficult and expensive to administer, but can result in more certainty of outcome

Carbon Taxes are levied on the carbon content of fuels. Carbon—present in hydrocarbon fuels like coal, petroleum, and natural gas—is released as CO2 when hydrocarbon fuels release their energy. Alternative sources of energy like wind and sunlight do not release CO2 as energy is released, although there may be carbon emissions involved in the production of wind and solar power systems. Since carbon is present in hydrocarbon fuels throughout various stages in their product cycle, a carbon tax can be levied on hydrocarbon fuels at multiple points. A tax can be incurred, for example, continuously as natural gas is burned for heat in a residence, or simply as it is produced.

Cap-And-Trade is a system in which an emission cap is set by issuing of a set number of emission credits. For example, a government could cap total carbon emissions at a given level by issuing permit allowances up to that level.

Emitters that can cheaply reduce emissions would do so and then sell their unused permits. This simultaneously rewards firms that are able to reduce their emissions below their permit cap as well as providing firms that face a high cost for reducing emissions a lower cost way of reducing system-wide emissions.

Some emissions trading systems include Offset Programs, which allow firms to earn and sell credit for projects that reduce emissions more than is required by regulation. Averaging programs set constant or declining emission rate standards and allow emitters to sell unused emissions allowances or save them for use in future years. Some cap-and-trade programs allow emitters to borrow emissions from their future selves in addition to Banking provisions that allow them to use unused emissions in future years.

Carbon Tax: The British Columbia Model

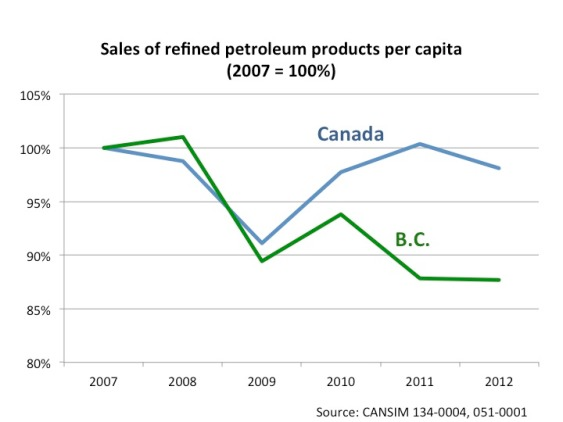

In the British Columbia Model, a carbon tax of $30 per ton of CO2is currently active. Enacted in 2008, the tax started at $10 per ton of CO2 and increased by $5 per year through 2012, when it reached the current price. Between 2007 and 2011, energy-related greenhouse gas emissions dropped by six percent overall, keeping pace with drops in Canada as a whole. The chief forces at play here are a market-wide shift from coal to gas outside of B.C., a natural gas boom in B.C., and the Great Recession.

Sales of refined petroleum products per capita, on the other hand, have dropped a full 15 percentage points since 2007, while rates in Canada as a whole are currently very close to 2007 levels. The stark effects of the recession are also apparent in the graph below.

Graph Courtesy of Sightline

In addition to the $30 per ton CO2 tax rate, the B.C. model has one more significant feature: it is Revenue Neutral. The additional tax revenue pulled in through the carbon tax is offset by broad tax cuts. In B.C., such cuts have included personal income tax cuts of $1.2 billion, low income tax credits of $997 million, business tax cuts of $3.1 billion, and other tax cuts of $329 million. All said, B.C.’s cumulative carbon tax revenue from 2008 to 2014 is roughly $5 billion, while tax cuts made in anticipation of the carbon tax revenue have totaled $5.7 billion.

The shortfall of $0.7 billion represents a key lesson to be learned in maintaining the balance between hard-to-predict carbon tax revenues and easier-to-predict tax cuts.

Another limit of B.C.’s carbon tax system is that the current carbon tax rate is not likely to get B.C. to its emissions goal; now that the tax rate has reached its cap, emissions are expected to begin rising again. At the same time, the gap between tax cuts and projected carbon tax income is expected to widen.

While revenue neutrality is a difficult balance to maintain, it presents a valuable gain to political feasibility. James Tansey, Executive Director of ISIS at the University of British Columbia, summarized the advantage of a revenue neutral tax: “It’s not a new tax, it’s a tax shift.” It’s much easier politically to pass a tax shift, he explained, than it is to pass a new tax.

Advocates in Washington argue that the institution of a revenue neutral carbon tax could go a long way towards normalizing the state’s tax structure. Instead of an income tax like other states, Washington has effectively spread out the tax burden across a range of other taxes, including exceptionally high sales, gas, and liquor taxes. “People feel nickel-and-dimed” by the complex network of taxes, argues Reuven Carlyle (District 36-D), Chair of the State’s House Finance Committee.

California Cap and Trade

In California, legislators have chosen to pursue a Cap and Trade model of carbon pricing. There are several features of the California Model of cap and trade that make it unique.

The California model, like many others, started with limited application and has slowly increased in scope and scale since 2006. The cap on emissions will continue to tighten until 2020. At the same time, California is slowly transitioning from distributing free permits to auctioning permits. California’s first cap and trade auction, held on November 14, 2012, raised $289 million

The money raised at auction is spent in two ways. Proceeds from investor-owned utilities go to programs that benefit those utilities’ ratepayers. Proceeds from the industrial and transportation sectors go towards furthering the state’s clean energy goals. Auctions are held four times a year.

By the end of 2015, the California model’s cap will encompass 85% of California’s emissions. Unlike the B.C. model, which currently covers about 70% of its emissions, the California model even includes a tax on electricity from out-of-state energy producers that emit greenhouse gasses. This is called a Carbon by Wire provision.

Like other cap and trade systems, the California model includes an arrangement for Banking. Banking allows entities to save unused permits for use in future years. This feature provides flexibility to the system. California has also included Offset Programs, which allow regulated entities to substitute qualifying offset programs for up to 8% of their emissions permits. The state is taking an hard line on the programs, requiring that the programs take place in the United States, have third-party verification, be in excess of regular program activities (a company’s reforestation program that has been in place since 1990, for example, would only qualify if it was expanded in excess of its regular operation), and be among a list of only five categories.

California has created a Permit Reserve, holding back a set number of emission permits from auction. If carbon prices climb over a certain point, the state will release these reserved permits to auction, helping to lower the price.

While it is still too early to declare the California model a success or failure, the price per metric ton of CO2 at California’s first auction was just over $10. This is nearly identical to the B.C. model’s starting rate.

Conclusion

Governor Inslee, in a recent executive order, assembled a panel of experts to design what he calls a “Cap and Market” system. Based on his executive order, it appears that he favors the California model over the B.C. model

In summary, both Cap and Trade and a Carbon Tax represent market tools for reducing rates of carbon emissions to socially optimal levels. Cap and Trade systems, like the California Model, place a cap on emissions by issuing or auctioning emissions permits and allowing carbon emitters to sell, bank, or use offset programs to earn more permits.

Carbon Tax systems, like the British Columbia Model, institute a predictable, transparent tax on CO2 emissions to reduce emissions levels. The tax rate in B.C. has slowly climbed from $10 per ton of CO2 emitted to its current rate of $30 per ton CO2 emitted. The B.C. model is Revenue Neutral, meaning that revenue from the carbon tax is offset by cuts in other tax areas, although B.C. has had trouble in the past in doing this.

While both systems have significant differences, “the tradeoff between a carbon tax and cap and trade has been exaggerated,” says James Tansey of the University of British Columbia. Both systems make use of existing market forces and represent significantly lower administrative costs and costs to efficiency than command and control methods.

References and Further Reading

Bauman, Yoram, Alan Durning, and Serena Larkin. “Cashing in Our Carbon.” Sightline, 2014. Web.

Hull, Dana. “13 things to know about California’s cap-and-trade program.” San Jose Mercury News, 22 Feb. 2013. Web.

IPCC, Glossary A-D: “Climate Price.” IPCC AR4 SYR 2007.

Reinard, J. “CO2 Allowance and Electricity Price Interaction.” International Energy Agency. 2007. Web.

“The Economists’ Statement on Climate Change.” Redefining Progress. 29 March 1997. Web.