By Calvin Quek, Head of Sustainable Finance at Greenpeace East Asia

China’s long-awaited and much touted Air Pollution Plan was released on Sept 12th, in response to the country’s “airpocalypse.”

Air pollution and environmental issues are quickly becoming top concerns among the Chinese public, sparking thousands of protests or “mass incidents.” The dire environmental issues are, according to China’s official news agency Xinhua, undermining the new administration’s vision of realizing the “China Dream”.

The key goals of the September plan are as follows:

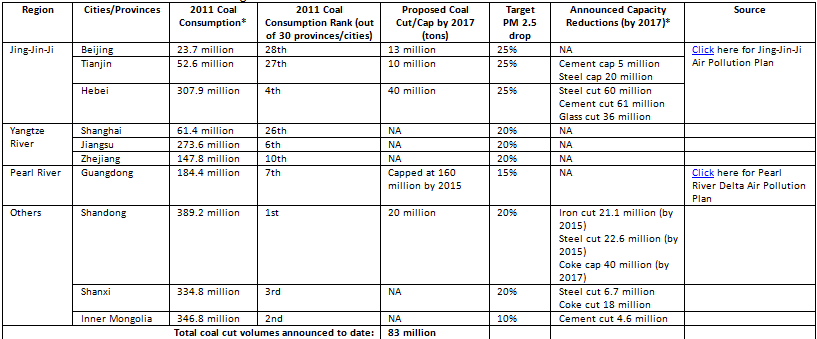

1.) Reduce PM 2.5 levels in the following regions, from 2012 levels by 2017. PM2.5 is a measure of fine particulate pollution. As PM2.5 levels rise, life expectancy drops.

a.) The “Jing-Jin-Ji” region (Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei): – 25% drop

b.) The Yangtze River Delta (Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang) – 20% drop

c.) The Pearl River Delta region (Guangdong) – 15% drop

2.) Reduce PM 10 levels in all 286 prefecture-level cities by at least 10% from 2012 levels by 2017

In addition, the plan broadly outlines how the provinces should go about achieving this targets, through the control of coal consumption, industrial and vehicular emissions, and the increased used of clean energy alternatives.

It calls for three main economic areas – Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei, Yangtze River Delta and Pearl River Delta – to peak and decline their coal consumption by 2017. It also bans the approval of new conventional coal-fired power plants in these key regions.

The ban on new coal-fired power plants covers China’s most important coal importing regions; the Pearl River Delta and Yangtze River Delta, responsible for more than 50% of thermal coal imports.

Given that tackling rampant and endemic overcapacity is one of the central government directives, we can see various cities and provinces, such as Tianjin, Hebei, Shandong and Shanxi announce cuts to heavy industry capacity, in parallel to their coal consumption reduction targets. Thus, these consumption cuts are no mere environmental issues, but really a structural readjustment of local provincial economies.

The below chart summarizes the latest figures and announcements.

Taking together the numbers have been announced, we can expect at least an 83 million ton cut in absolute coal consumption from 2012 levels in 2017.

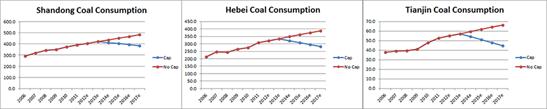

Compared to the past several years, the air pollution plan and its coal consumption cuts is a significant turnaround, particularly in the heavily industrialized northeastern regions of Hebei, Shandong and Tianjin, which have seen coal consumption grow at an 6% annualized growth rate from 2006 to 2011.

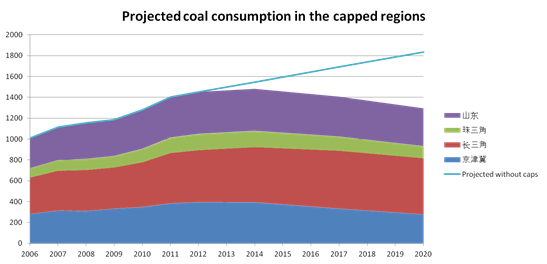

These coal caps reverse the trajectory of growing coal demand, especially in major import centers. Mapped out to 2020, these caps could mark a reduction of ~500 million metric tonnes from the baseline projection.

Given that China is the world’s largest market for imported coal, China’s drive to cut coal consumption is having significant effect on global coal exporters. In Australia, governments are beginning to wrestle with the risks and challenges of over-investment in a coal export economy.

The emerging Wall St consensus is that new coal infrastructure is a risky bet, at best, with Bernstein, Goldman Sachs, Citibank, HSBC, and Deutsche Bank all publishing very bearish reports.

So, why do US coal companies continue to pursue these export terminal projects? In short, they don’t have many other options on the table. Coal use is falling in the US and the industry is in decline.

Compare the stock performance of Peabody Energy (BTU, in blue) and Arch Coal (ACI, in red) against the Dow Jones Index (in yellow) since early 2011, right after the Gateway Pacific backers applied for federal permits:

These coal export terminal proposals may more closely resemble existential fights for the shrinking US coal industry than rational economic opportunities.